UPDATE: Screenshots of the al-Marri opinion added.

Orin Kerr has some thoughtful objections to the recent Fourth Circuit case (Al-Marri v. Wright) holding that the U.S. government cannot hold a lawful visitor to this country in "indefinite military detention" simply by declaring him an "enemy combatant". According to the Fourth Circuit, the government can do many things — including transferring the detainee to civilian authorities to face criminal charges, initiating deportation proceedings, holding him as a witness in a grand jury proceeding or detaining him for a limited period of time under the Patriot Act, an anti-terrorism law — but (according to the Fourth Circuit) it cannot simply hold the guy without trial or due process indefinitely.

In his first post, Kerr lays out a hypothetical scenario (something that law professors like Kerr are exceedingly good at) to highlight the implications of the al-Marri holding:

An Al-Qaeda cell of five individuals, all citizens of Qatar, enter the United States on student visas. The cell members’ plans are to detonate a "dirty bomb" in New York City, and they rent a hotel room in Jersey City, New Jersey (just across the river) to build the dirty bomb. One of the hotel employees thinks the group is suspicious, and he calls up the local police and tells an officer that there is a group of Arab men in the hotel staying in one room and acting very secretively.

The officer visits the hotel when the men are out one day and he requests that the hotel employee show him the room. The employee agrees; he opens the door with his key and shows the officer inside. They immediately see the bomb-making materials along with several photographs of Osama bin Laden and the 9/11 attacks taped to the walls. The officer contacts the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security. An hour later, the FBI has obtained a search warrant for the room and arrest warrants for the five men.

The men are arrested and charged criminally. A search of the hotel room discovers all the bomb-making materials. The room search also uncovers videotapes the men made celebrating their pending attack; the men each spent a few minutes on tape describing what attacks they will execute and hoping and praying that the streets of New York will "run red with Jewish and imperialist blood."

But there’s a major problem with the criminal case: The evidence against the cell members was obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment. Under Stoner v. Califonia, the men have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the hotel room and the hotel clerk lacks authority to consent to a law enforcement search. As a result, the evidence against the five men was obtained in violation of their Fourth Amendment rights. The evidence — including the videotapes in which they each celebrated the attacks and confessed to their plans — must be suppressed.

So what should the government do?

Kerr points out that under the al-Marri holding, the government can either deport the men, or set them free — even though it’s clear (from the facts of the hypothetical) that they are al-Qaeda members.

Kerr points out that under the al-Marri holding, the government can either deport the men, or set them free — even though it’s clear (from the facts of the hypothetical) that they are al-Qaeda members.

The comments section is interesting (albeit wonkish) reading, particular the response from Professor Lederman. Together, they demonstrate the conceptual tug between the concepts of due process and the desire to catch the bad guys.

Kerr follows up the next day with an equally intriguing post, highlighting the problems in how the government treats, or should treat, various types of defendants:

Consider the following persons detained by the United States in various circumstances:

1. U.S. citizen seized in Afghanistan, suspected of helping the Taliban forces in battle.

2. U.S. citizen suspected of blowing up a federal building as part of a plot to overthrow the U.S. government.

3. Suspected German soldier seized on the battlefield on D-Day in 1944.

4. Frenchman seized on the battlefield on D-day in 1944 suspected of helping the Germans.

5. Suspected crack cocaine dealer arrested in New Jersey.

6. Suspected Al Qaeda terrorist seized in U.S. after entering the U.S. to launch another 9/11.

7. Suspected Al Qaeda terrorist seized in Iraq after entering Iraq to join fight against U.S.

8. U.S. citizen who lives in Detroit and suspected to be a supporter of Al Qaeda; evidence suggests he sent $10,000 to a "charity" that is really a fun to help Al Qaeda launch more attacks in United States.

9. Egyptian citizen in the U.S. on a tourist visa seized in the U.S. on suspicion of planning attacks against a U.S. military base.

10. U.S. soldier in World War II suspected of being a double agent for the Germans.From the standpoint of policy, which of these cases should be handled under the "war" rules and which under the "crime" rules? And how do you tell the difference? My sense is that most people would say that there are difficult line-drawing issues here. Not everyone on this list should be dealt with under the "war" rules; not everyone on this list should be dealt with under the "crime" rules.

If one thing is clear about Kerr’s posts and the discussions they’ve generated, it is that the legal system in this country lacks cohesiveness when it comes to matters of "crime" during times of "war" — i.e., who is a "criminal" and who is an "enemy" in the eyes of the law?

Kerr concludes:

What I found odd about Al-Marri is that it seems to treat most cases of Al Qaeda terrorists here to attack us as crime cases. It seems to me like an effort to bypass the Supreme Court’s sliding scale war-crime framework in Hamdi and to replace it with a regime in which all the Al-Qaeda bad guys are forced into the crime model. I don’t think this is the right box, which is why I see the Al-Marri framework as odd.

Anyway, that’s my take. I realize a lot of commenters disagree, but I hope we can approach the disagreements in good faith with the understanding that we are all trying to grapple as best we can with a very difficult set of problems.

There’s no easy answer, but Kerr seems to think that al Qaeda terrorists ought to be treated as military "enemies" (and subject to military laws regarding detention) because "they see themselves as enemies", rather than criminals. While that may be true, I don’t see that as being very relevant. People like Timothy McVeigh and/or the Unabomber might also be declaring their own "war" on the United States, yet we process them through the civilian, rather than the miltary, criminal framework.

There’s no easy answer, but Kerr seems to think that al Qaeda terrorists ought to be treated as military "enemies" (and subject to military laws regarding detention) because "they see themselves as enemies", rather than criminals. While that may be true, I don’t see that as being very relevant. People like Timothy McVeigh and/or the Unabomber might also be declaring their own "war" on the United States, yet we process them through the civilian, rather than the miltary, criminal framework.

Whatever one thinks, it’s clearly an issue with which this country will have to reconcile.

UPDATE: I would be remiss in not including Glenn Greenwald’s take:

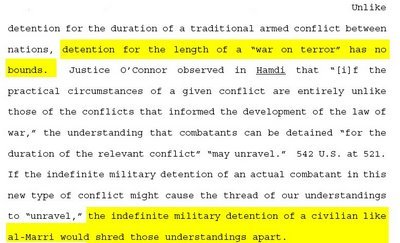

The decision (.pdf) of the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals in the Al-Marri case technically rests on narrow grounds of statutory construction regarding the scope of the Military Commissions Act, but it is actually quite extraordinary in the broader constitutional principles it affirms and the tone it uses to apply them.

Next to the Padilla travesty, the Government’s treatment of Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri — just on the facts alone — may very well be the single most despicable instance of deliberate denial of the most basic liberties. I have written about the facts and circumstances of al-Marri’s detention here.

I really recommend reading (at least) the first 11 pages of the court’s decision, where the court sets forth in very stark and clear terms exactly what we have done to al-Marri. I recall the sensation, back in law school, of reading legal opinions from various periods of time throughout our country’s history which began by recounting the government’s behavior and finding it difficult to believe that any government could engage in such conduct without provoking a massive backlash (and sometimes it did).

That is the reaction which this opinion provokes (even though the facts are familiar). No matter how many times one thinks about it, reads or writes about it, it never ceases to amaze — literally — that our government has asserted the power to imprison people, including those on U.S. soil, and keep them locked up for years and years, indefinitely, without so much as charging them with any crime or even allowing them access to lawyers. And that is to say nothing of what is done to them while being held completely incommunicado. That was just a line that one thought the American Government could not cross without enormous backlash. Yet our government has done exactly that for years — and has spawned a set of presidential candidates vowing to continue doing so at least as aggressively, if not more so — without much protest at all.

And here is the background on al-Marri:

In 2001, al-Marri, a citizen of Qatar, was in the United States legally, on a student visa. He was a computer science graduate student at Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, where he had earned an undergraduate degree a decade earlier. In Peoria, he lived with his wife and five children.

In December, 2001 he was detained as a "material witness" to suspected acts of terrorism and ultimately charged with various terrorism-related offenses, mostly relating to false statements the FBI claimed he made as part of its 9/11 investigation. Al-Marri vehemently denied the charges, and after lengthy pre-trial proceedings, his trial on those charges was scheduled to begin on July 21, 2003.

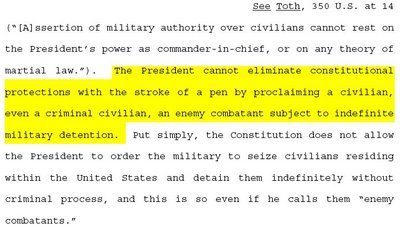

But his trial never took place, because in June, 2003 — one month before the scheduled trial — President Bush declared him to be an "enemy combatant." As a result, the Justice Department told the court it wanted to turn him over to the U.S. military, and thus asked the court to dismiss the criminal charges against him, and the court did so (the dismissal was "with prejudice," meaning he can’t be tried ever again on those charges). Thus, right before his trial, the Bush administration simply removed Al-Marri from the jurisdiction of the judicial system — based solely on the unilateral order of the President — and thus prevented him from contesting the charges against him.

Instead, the administration immediately transferred al-Marri to a miltiary prison in South Carolina (where the administration brings its "enemy combatants" in order to ensure that the executive-power-friendly 4th Circuit Court of Appeals has jurisdiction over all such cases). Al-Marri was given the "Padilla Treatment" — kept in solitary confinement, denied all contact with the outside world, including even his own attorneys, not charged with any crimes, and given no opportunity to prove his innocence. Instead, the Bush administration simply asserted the right to detain him indefinitely without so much as charging him with anything.