Jamal Khashoggi, a well-known Saudi Arabian journalist and Washington Post columnist who has been critical of his country’s government, vanished last week.

His disappearance is straining Turkey-Saudi relations and could complicate Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s recent attempts to recast his government as forward-thinking and reform-minded — as well as his country’s close relationship with the US.

The 59-year-old veteran journalist was last seen on October 2 walking into the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul. He was there to obtain a document verifying his divorce so that he could marry his Turkish fiancée.

But what happened next is a mystery.

Turkish officials have said they have “concrete” evidence that Khashoggi never left the building and was murdered there; some have even put forth gruesome theories of how his body may have been dismembered and smuggled out.

The Saudi government, however, says it had nothing to do with his disappearance and maintains that he left through a back entrance, though it has provided no evidence to support that.

A Saudi official told me in an email on Monday that “Jamal’s disappearance is a matter of grave concern to us, and we categorically reject any allegations of involvement in his disappearance.”

Murdered WaPo journalist, who was killed in the Saudi consulate in Istanbul, recorded the audio of his death via his Apple watch. His location was tracked as well. https://t.co/A3riiitNGb

— RynheartTheReluctant (@TheRynheart) October 12, 2018

Amid the ongoing investigation, relations between Saudi Arabia and Turkey have quickly soured. The mystery is shaking Washington as well: Khashoggi is a US resident and had been living in self-imposed exile in Virginia for about a year — fearful, he said, that the Saudi government would target him for his dissident views.

If he was indeed murdered by his own government, it raises bigger questions about the safety of journalists, freedom of speech, and the future of Saudi relations with Turkey, the US, and others.

WaPo reported: “Before Khashoggi’s disappearance, U.S. intelligence intercepted communications of Saudi officials discussing a plan to capture him, according to a person familiar with the information.”

— Jake Tapper (@jaketapper) October 12, 2018

I asked ODNI: Why wouldn’t the US warn him?

ODNI: No comment.

Khashoggi used to enjoy close ties to the Saudi royal family. In the early 2000s, he served as an adviser to Saudi Prince Turki bin Faisal, the former director of Saudi Arabia’s intelligence agency, while the prince was the ambassador to Washington. Khashoggi also worked as the editor of a Saudi newspaper, Al Watan. But in recent years, he had taken a more critical tack, criticizing the leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (also known as MBS).

The 33-year-old crown prince has tried to paint himself as a reformer by loosening restrictions on women driving and opening up cinemas in the Kingdom, but he’s also led a purge of opposition within his government under the guise of a crackdown on corruption and championed a bloody, brutal war with Yemen that’s left tens of thousands dead.

And despite his reforms, MBS hasn’t shown any willingness to tolerate political dissent or free speech. He’s even arrested some of the activists who championed the reforms he’s pushed through.

In June 2017, Khashoggi, fearing arrest, left the country. He resettled in the US, where he spent the past year living in self-imposed exile.

Khashoggi became a frequent contributor to publications like the Washington Post’s global opinions section and continued to criticize the Saudi government from afar. In a column published last September titled “Saudi Arabia wasn’t always this repressive. Now it’s unbearable,” he wrote of how his hope that the crown prince would be a reform-minded voice has now given way to fear of repression.

“I have left my home, my family and my job, and I am raising my voice,” he wrote. “To do otherwise would betray those who languish in prison. I can speak when so many cannot. I want you to know that Saudi Arabia has not always been as it is now. We Saudis deserve better.”

Khashoggi also expressed concern about being targeted by the Saudi government for his views, telling journalist Robin Wright in August that the country’s new leadership would like to “see me out of the picture.”

And just three days before he disappeared into the Saudi consulate in Turkey, he told BBC Newshour in an off-air interview that he doubted he’d ever be able to return to his home country. “I don’t think I’ll be able to go home,” he told the BBC, saying that in Saudi Arabia, “the people who are arrested are not even dissidents.”

Three days later, his worst fears may have been realized.

Khashoggi first went to the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul on September 28 to file paperwork needed for his upcoming wedding to a Turkish woman, Hatice Cengiz.

On October 2, he returned to the Saudi Consulate at around 1 pm, according to Cengiz. She told the Washington Post that she waited for him by the gate outside, but that several hours later, even after the consulate had closed, there was still no sign of him.

Cengiz said that she called the consulate and spoke to a guard, who told her there was no one inside. She then called the police, as well as an adviser to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, as Khashoggi had instructed her to do if anything should happen to him.

After several days of confusion and no sign of Khashoggi, Turkish officials said on Sunday that they believed the journalist had been murdered, according to the Washington Post.

Yasin Aktay, a friend of Khashoggi’s and adviser to the Turkish president, told Reuters that he believed Khashoggi had been killed inside the Saudi Consulate, and that Turkish authorities think 15 Saudi nationals were involved.

Turan Kışlakçı, the head of the Turkish-Arab Media Association and a friend of Khashoggi’s, told the Associated Press that Turkish officials he’d spoken with said Khashoggi had been murdered “in a barbaric way” and that they had evidence which they had not yet released. Other anonymous Turkish officials told news outlets that his murder had been “preplanned” and that his body had been moved from the consulate.

On Monday, Turkey requested an official search of the Saudi Consulate in Istanbul to find evidence of the apparent crime. Saudi officials said they would allow the consulate to be inspected.

Erdoğan has weighed in as well, saying that the disappearance was “very, very upsetting.” During a press conference on Monday, the Turkish president said the onus was on Saudi Arabia to prove that Khashoggi had indeed left the consulate. “The consulate officials cannot save themselves by simply saying ‘he has left,’” Erdogan said, according to Reuters.

In a letter to journalists on Tuesday, Saudi Ambassador to the US Prince Khalid bin Salman wrote that the Saudi government had sent a security team to work with Turkey to uncover what happened and were cooperating with Turkish authorities.

“Jamal has many friends in the Kingdom, including myself, and despite our differences, and his choice to go into his so called ‘self-exile,’ we still maintained regular contact when he was in Washington,” he wrote. “Jamal is a Saudi citizen whose safety and security is a top priority for the Kingdom, just as is the case with any other citizen.”

But on Wednesday, the Washington Post reported that the Saudi Crown Prince had devised a plan to lure Khashoggi back to Saudi Arabia and detain him, according to US intelligence intercepts of Saudi communications.

The Post also reported that two planes carrying a team of 15 Saudi men arrived in Istanbul from Riyadh on the day that Khashoggi disappeared, and left later that day. Experts have speculated that these men were part of an effort to capture him and bring him back to the Kingdom — an effort that may have gone badly wrong.

But here’s where it gets tricky.

Possible Saudi involvement in the disappearance—and alleged murder—of the Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi presents the U.S.-Saudi relationship with its greatest crisis since 9/11. If the Saudis are proven guilty of this heinous crime, it should change everything about the United States’ long-standing relationship with Saudi Arabia. Regrettably, it probably won’t.

The administration’s identification with Mohammed bin Salman, as a modernizer determined to open up the kingdom and tame its religious extremism has now been undermined by a crueler reality—that of a ruthless, reckless, and impulsive leader willing to repress and silence his critics at home and abroad.

Whatever happened to Khashoggi is first and foremost on the Saudis. But in kowtowing to Riyadh in a fanciful effort to make it the centerpiece of U.S. strategy in the Middle East, the Trump administration has emboldened MbS, as the crown prince is known, created a sense of invincibility, and encouraged him to believe there are no consequences for his reckless actions. And it is likely, unless confronted with incontrovertible evidence of Saudi responsibility for Khashoggi’s death or serious pressure from Congress, the president would be reluctant to impose them even now.

Trump’s enabling of Saudi Arabia began even before he became president. He talked openly on the campaign trail about his admiration for Saudi Arabia and how he couldn’t refuse Saudi offers to invest millions in his real-estate ventures. His predecessors may have gone to Mexico or Canada for their first foreign foray; Trump chose Saudi Arabia. In a trip carefully choreographed by his son-in-law Jared Kushner, who quickly established close personal ties with the soon-to-be crown prince, Trump was feted, flattered, and filled with hopes for billions in arms sales and Saudi investment that would create jobs back home. Trump’s aversion to Obama’s Iran deal also fueled the budding romance. Trump used his anti-Iranian animus (even while he boasted he’d make a better deal with the mullahs) to energize his ties with Riyadh, and MbS was only too happy to exploit his eagerness. Reports that MbS saw Trump’s team, particularly Jared Kushner, as naïve and untutored should have come as no surprise.

Previous administrations—both Republican and Democratic—also pandered to the Saudis, but rarely on such a galactic, unrestrained, and unreciprocated scale. Through its silence or approval, Washington gave MbS—the new architect of the risk-ready, aggressive, and repressive Saudi policies at home and in the region—wide latitude to pursue a disastrous course toward Yemen and Qatar. The administration swooned over some of MbS’s reforms, while ignoring the accompanying crackdown on journalists and civil-society activists. Indeed, The Guardianand other outlets reported that MbS told Kushner in advance of his plans to move against his opponents and wealthy businessmen, including some royals, in what might be termed a “shaikhdown.”

The greatest foreign-policy success of MbS’s first year in power was his success at capturing of the heart and mind of the president. And there’s little doubt that U.S. permissiveness and willingness to give the Saudis the benefit of the doubt emboldened MbS to act without regard to external constraints and with the confidence that U.S. support could be taken for granted.

The U.S. has important national interests in the stability of Saudi Arabia, and Trump’s embrace of MbS has brought some returns. The upsides of U.S. support for MbS, however, are overwhelmed by the downsides of empowering him to screw up whatever he touches. Over the past two years, the policies pursued by the crown prince have undermined important American interests. For all the investment the administration has made in the U.S.-Saudi relationship, we are getting precious little in return.

In May of 2017, the Saudis promised to buy $110 billion worth of additional U.S.military weapons and equipment.Trump has cited those arms sales as a reason not to pressure the Saudis over Khashoggi’s disappearance. But there’s a lot less here than meets the eye.

The Saudis have also opened their checkbook to support U.S. aid initiatives in the Middle East. In response to American prodding, they have offered $100 million in reconstruction assistance to Syria. This is a welcome step, but they could be doing much more, as, for example, they’ve been doing in Iraq.

It is hard to assess the value of Saudi counterterrorism cooperation because most of it operates under a cloak of secrecy. Whatever contributions Saudis make in intelligence sharing and law enforcement, though, serves Saudi interests. It is not being proffered as a favor to the United States.The same is generally true for Saudi energy policy, where decisions on oil production and exports are largely driven by market forces and the kingdom’s own needs.

Against these modest gains, MbS’s mistakes weigh heavily. A Saudi-led military coalition is waging an inhumane campaign against the Iranian-supported Houthi rebels in Yemen, giving al-Qaeda and isis greater room to maneuver and handing Iran greater opportunities to spread its influence in Yemen. The wanton killing and destruction, much of it done with U.S. military support, has further sullied America’s reputation. The Saudis have resisted attempts by the UN to broker a political settlement of the dispute as well as UN investigative efforts to establish accountability for possible Saudi war crimes.

The administration’s efforts to turn the Gulf Cooperation Council into an effective anti-Iranian coalition have foundered over the bitter and unnecessary fight that Saudi Arabia (and the UAE) have picked with Qatar. Their joint blockade of Qatar pushed the gulf state to strengthen its ties with Iran, and has greatly complicated administration efforts to confront the Iranian challenge in the region by turning the GCC into a more military force and forming a new “Middle East Strategic Alliance.” The Saudis have made a number of unreasonable demands on Qatar, while rejecting U.S.efforts to resolve the dispute.

The Saudis have also dampened Kushner’s hopes for making the “deal of the century.” King Salman made it clear to the White House that Saudi Arabia will not support the new American Middle East peace plan unless it explicitly designates East Jerusalem as the capital of an independent Palestinian state, a demand Netanyahu’s government is likely to reject.There was always too much magical thinking in the Trump administration’s conception of what the Saudis would do to reach out to Israel and pressure the Palestinians when it came to peacemaking. Now in the wake of the Khashoggi affair, Saudi decision-making on this and other issues may become even more inward looking.

All of this helps to explain why the Saudi role in the disappearance of Khashoggi is such a critical inflection point in U.S.-Saudi relations. Unlike 9/11, where there’s no compelling evidence that the senior Saudi leadership had foreknowledge or played a role in the attacks, the killing of Khashoggi could not have taken place without the express approval of the crown prince. Even if those looking for a way to defuse this crisis believe it can be dismissed as a rogue operation and those who perpetrated the killing handed over for trial (most likely magical thinking) nobody would ever believe that MbS didn’t bear responsibility for the affair. This single act—the culmination of a series of repressive actions against women activists, journalists, and family members—will make it nearly impossible to continue to mask the obvious: MbS may be committed to serious reform, but it will be directed from the top down by a ruthless and inexperienced leader who brooks no criticism or dissent and who’s prepared to go to murderous lengths to eliminate any opposition. The message to Saudis who believed they could criticize MbS with impunity was that no one can protect them. If the allegations of Khashoggi’s horrific killing are confirmed, it will mark MbS permanently and make it impossible for the administration to tout his reformist credentials.

Still, Saudi money can be persuasive. Next week, high-level U.S. financiers and government officials have been invited to the MbS-sponsored Davos in the Desert Conference to be held at the very same Ritz-Carlton where the regime detained and bilked scores of wealthy and influential Saudis under the guise of an anticorruption campaign. Who attends and who doesn’t may provide some measure of how the Khashoggi disappearance is affecting the kingdom. As of this writing, major media outlets (including CNN, NBC and the NY Times) as well as Richard Branson are skipping the conference. On the other hand, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchen is going.

Statement from Bloomberg spox on FII: “Bloomberg will no longer serve as a media partner for the Future Investment Initiative. As we do with every major event in the region, we plan to cover any news from our regional news bureau."

— Max Tani (@maxwelltani) October 12, 2018

NEW: SAUDI ARABIA has paid nearly $9M to lobbying firms so far this year. But at least one firm ended its contract today, & others are considering following suit, as the country faces mounting backlash over its alleged assassination of JAMAL KHASHOGGI. https://t.co/7rUXrqx2Gk pic.twitter.com/FiIPvBHsvh

— Kenneth P. Vogel (@kenvogel) October 12, 2018

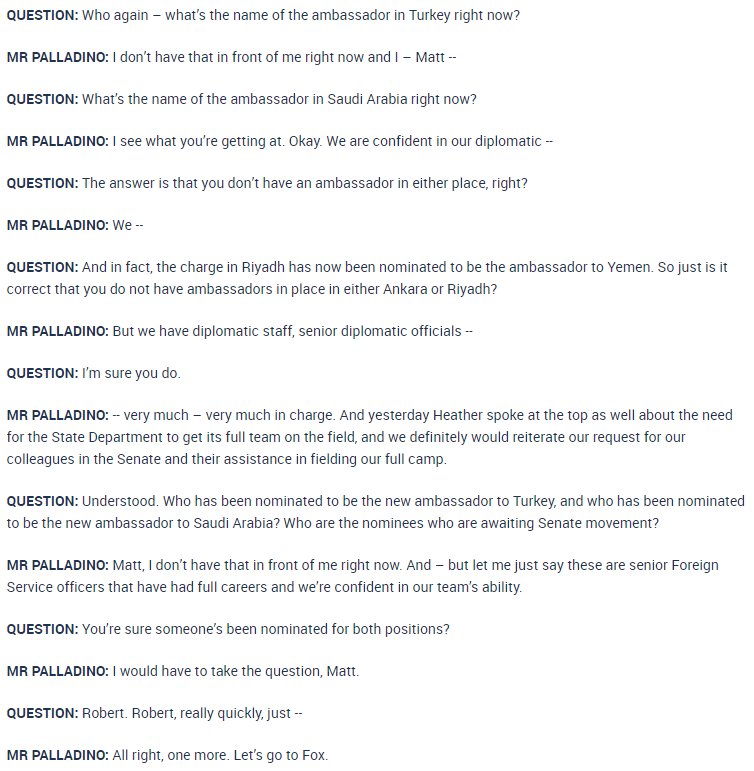

All of this is complicated by the fact that Trump has not assigned any ambassadors to Saudi Arabia or Turkey. Look at this notable exchange between a reporter and the State Department spokesman (Palladino)

Outside of the administration, pressure is growing. Congress recently fell four votes short of suspending U.S. military assistance to Saudi Arabia over civilian casualties in Yemen. A letter sent Wednesday to Trump by a bipartisan group of legislators triggered the Global Magnitsky Act, which will force the administration to investigate Khashoggi’s disappearance, and if the Saudis are found complicit, to impose sanctions. And journalists—having lost one of their own—will continue to be seized with this issue.

The question that remains to be answered, though, given the executive branch’s control of foreign policy, is how the Trump administration will respond over time. Will it recognize that the U.S.-Saudi relationship is out of control? That the Saudis are pursuing interests that do not coincide with ours, and that the Saudi leadership seems to feel confident that it can continue to use and abuse Washington’s support without attention or regard to American values or interests? And will it—out of frustration over Saudi behavior—ask the same question posed by Bill Clinton to his aides after his first meeting with Benjamin Netanyahu: “Who’s the fucking superpower here?”

On paper, MbS is committed to an agenda that would benefit Saudi Arabia and the region, particularly his seeming determination to moderate the extremist strain of Islam that the Saudis have exported for years, and to foster the kingdom’s emerging and largely covert ties with the Israelis. An enlightened and experienced leader pursuing reform in a political culture and region resistant to change would usually be worthy of U.S.support. But an impulsive and reckless 33-year-old leading a regime that’s repressing and imprisoning his subjects at home and perhaps killing them abroad is not. America cannot create the former; but it certainly has no business empowering the latter. The Trump administration should not fail to recognize the difference.

I still want to know how much money the Trump Organization has been paid by Saudi entities since Election Day 2016

— David Frum (@davidfrum) October 12, 2018

FARA filings revealed Saudi Arabia paying Trump Hotel DC ~$270k as part of one lobbying firm's foreign influence campaign https://t.co/FxhIg7Aqk7 pic.twitter.com/wvtSquqDb9

— Anna Massoglia (@annalecta) October 12, 2018

Trump Hotel room revenue rose 13% in first 3 months of 2018 after a 2 year decline due to "last minute visit" by Saudi Crown Prince. Trump claims to donate foreign govt profits to Treasury under ethics agreement—but keeps details secret https://t.co/LQXUBLf4O8 pic.twitter.com/XIFfAEjTZ4

— Anna Massoglia (@annalecta) October 12, 2018